The principles of acupuncture are firmly grounded in science, and you don’t need Chinese philosophy either to make it work, or to practice it, says a leading medically trained acupuncturist. Dr Adrian White, who is editor in chief of the scientific journal Acupuncture in Medicine, was speaking at the launch of the journal’s transfer to publication by BMJ Group after 27 years of publication with the British Medical Acupuncture Society (BMAS).

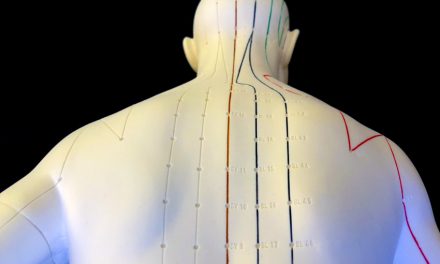

“One of the major problems facing medical acupuncture is the preconceived notions both the public and healthcare professionals have of it,” he said. “The perception is that acupuncture is still all about chi and meridians.”

This view has hindered its acceptance among healthcare professionals, and its wider use as a valid addition to pain control in conditions, ranging from nausea to arthritis, as well as after surgery, he contends.

“In the past it was easy for doctors and scientists to dismiss acupuncture as ‘highly implausible’ when its workings were couched in talk of chi and meridians. But it becomes very plausible when explained in terms of neurophysiology,” he explains.

Unfortunately, the scientific approach just isn’t as sexy,” he continues. “Many people, including practitioners and the public, have held on to the traditional explanations.”

And there’s plenty of scientific evidence, which has been building up for the past 30 years, to show that acupuncture stimulates the nerves in the brain and spinal cord, releasing feel good chemicals, such as opioids and serotonin. The research also shows that a needle placed outside of the traditional meridians will have an impact.

“Points don’t have any magical properties; they are simply convenient locations to needle,” he says.

Clinging to the traditional approach also stymied good quality research, because needling outside the meridians is often used as a comparator. “This misunderstanding has been a fundamental flaw in the design of many acupuncture studies,” comments Dr White.

Shrouding acupuncture in the mystery of Chinese philosophy has also prevented healthcare professionals from providing acupuncture themselves.

“[They] already know how to diagnose, and they already know a great deal about anatomy and physiology, so they can easily learn to practice acupuncture safely and effectively,” after a short foundation course, of the type provided by BMAS, he says.

“The aim of Acupuncture in Medicine is to build up the evidence base for acupuncture’s place in the modern health service,” says Dr White.

While it may not be a cure all, acupuncture does have a place, and is a relatively inexpensive approach to common conditions that can be difficult and often costly to treat, he says.

Recent Comments